+-

LOK / 2024

From Major Project S2 2024

Supervised by Anna Jankovic

Programme Reuse Centre, Nursery, Large Format Retail Residential

abstract:

Architecture’s current material paradigm is heavily disassociated from the material reality of its formation. There is a distinct disregard for the places in which the matter of architecture comes from and the effect it has on that material landscape and the broader territory. It is deemed not in the scope of the object of architecture. Instead, we elect to view a sanitised product devoid of a material history. This disregard has the profession as a significant component of biodiversity and climate collapse of which our industry holds a level of culpability. To reroute, we must consider the shadow places in which architecture depends for formation as part the lexicon and responsibility of the architect.

This project attempts to figure how architecture might begin to shift our current material culture, examining the labour of the architect and how we might find agency here. It rejects an idea ofpassivity in this role nor sees it exonerated as one lacking sufficient agency.

+_ is the pursuit of seeing the additive object and the subtractive object of architecture, acknowledging the effects of both. The project adopts a framework of the path of material from production, to market, to assembly it steps through a series of details that speak broadly to the material matter, material landscapes and our impact on them. It seeks to question how architecture might express a broader care through its labour and seed a less destructive industry.

+

-

![]()

oil vernacular

Architecture is typically conceived as an additive operation, adding material forms upon a site, the architect’s currency in this task is bringing to market a mass of material, drawn and specified. Little attention, however, is given to the subtractive operation that precedes the additive, deemed not in scope. One indeed cannot happen without the other. The aim of this project is to reintroduce the effects of the subtractive into the lexicon and the responsibility of the architect.

The use of fossil fuels and their resultant technological epoch meant access to cheap, consistent energy, combined with a global base of cheap labour, has enabled materials to be manufactured using energy-hungry processes from disparate components and transported across the world. This material culture can be measured in mineral extraction, degradation and disposability with fundamental disregard for the land and shadow places of subtraction we depend upon, and the effects we have on them. This system is typified by dominion over ecosystems that should be acknowledged as colonialist and capitalist violence.

Our contemporary construction paradigm is dependent on this violence and relies on it remaining opaque from those who consume and determine its form, electing to view the materials of architecture as sanitised products rather than the material reality of their production.

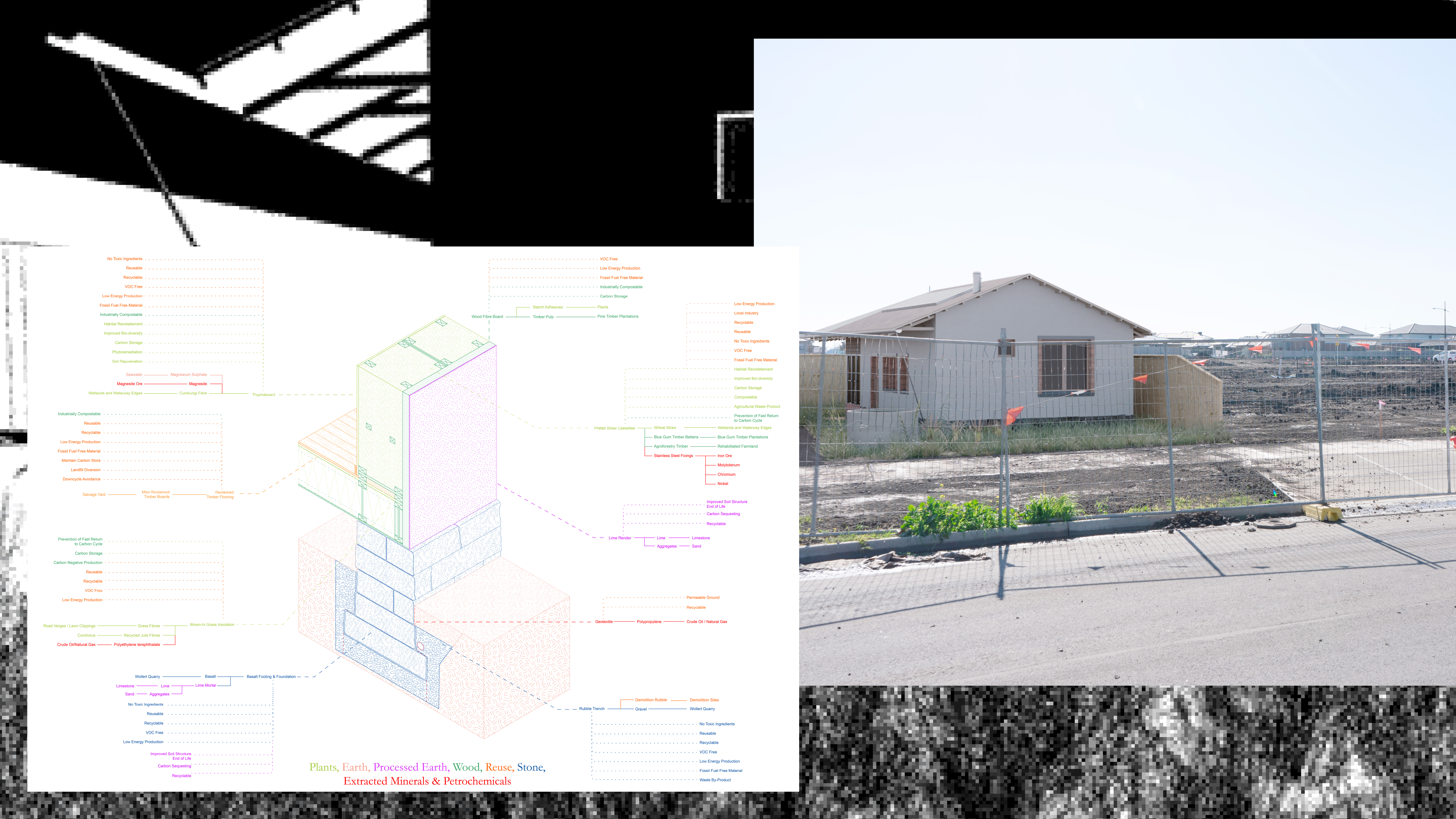

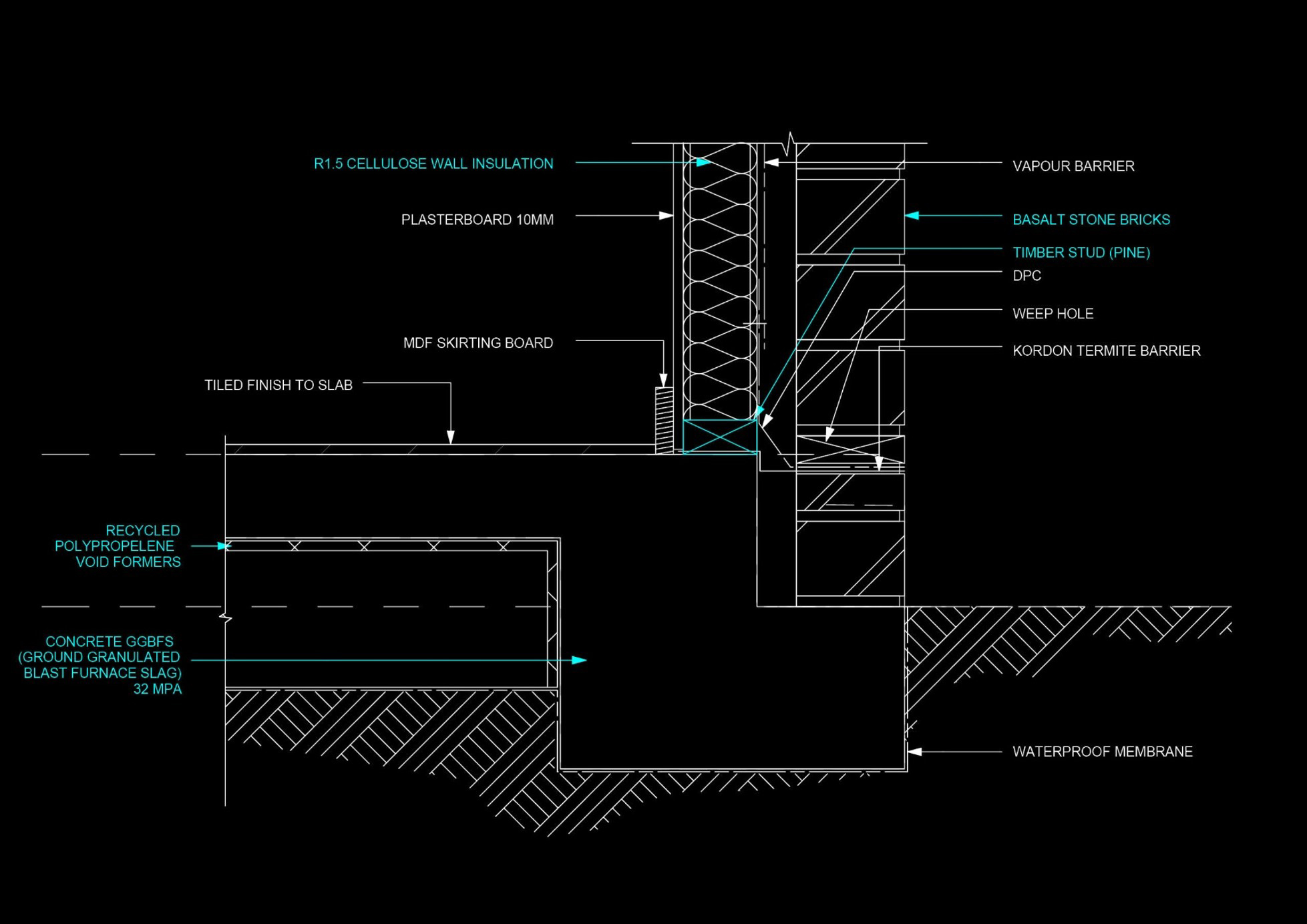

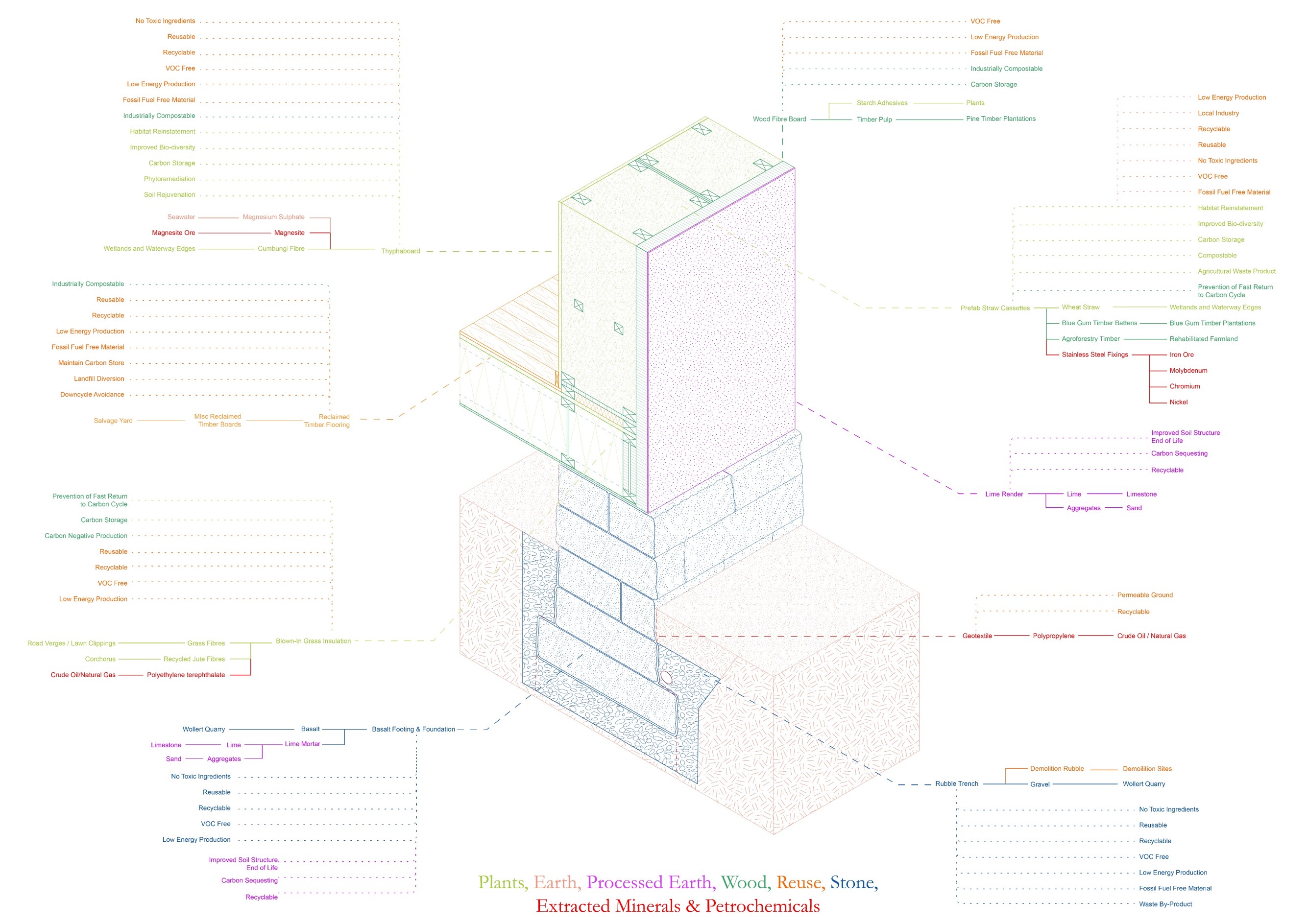

To begin to unpack the problem of the oil vernacular, we begin with a house that typifies it. A steel frame brick veneer home, a carbon form enabled by the current energy paradigm of fossil fuels. To access the violence induced through the production of this home, the fidelity of detail must be analysed. While this mode of communication is often dismissed as neutral technical instruction, its reality is that the materials drawn and specified cause a chain of extraction, manufacturing and labour that begins with lines and words on a page.

To begin to unpack the problem of the oil vernacular, we begin with a house that typifies it. A steel frame brick veneer home, a carbon form enabled by the current energy paradigm of fossil fuels. To access the violence induced through the production of this home, the fidelity of detail must be analysed. While this mode of communication is often dismissed as neutral technical instruction, its reality is that the materials drawn and specified cause a chain of extraction, manufacturing and labour that begins with lines and words on a page.

Peering into the detail, we see that its material reality is a political act, energy-intensive products, which cause massive amounts of carbon emissions and represent fossil fuel dependency, habitat loss, toxicity, biodiversity collapse, water and air pollution.

Examining the component parts, we would see 26 base materials, 23 separate mineral extraction sites and 16 fossil fuel-dependent materials

In totality, we see 10 million kWh of energy, 4.6 million litres of water 276,000kg of CO2. The whole of which has its matter manufactured, transported and constructed using fossil fuels with usage and form that ingrains fossil fuel dependency through performance.

by the numbers:

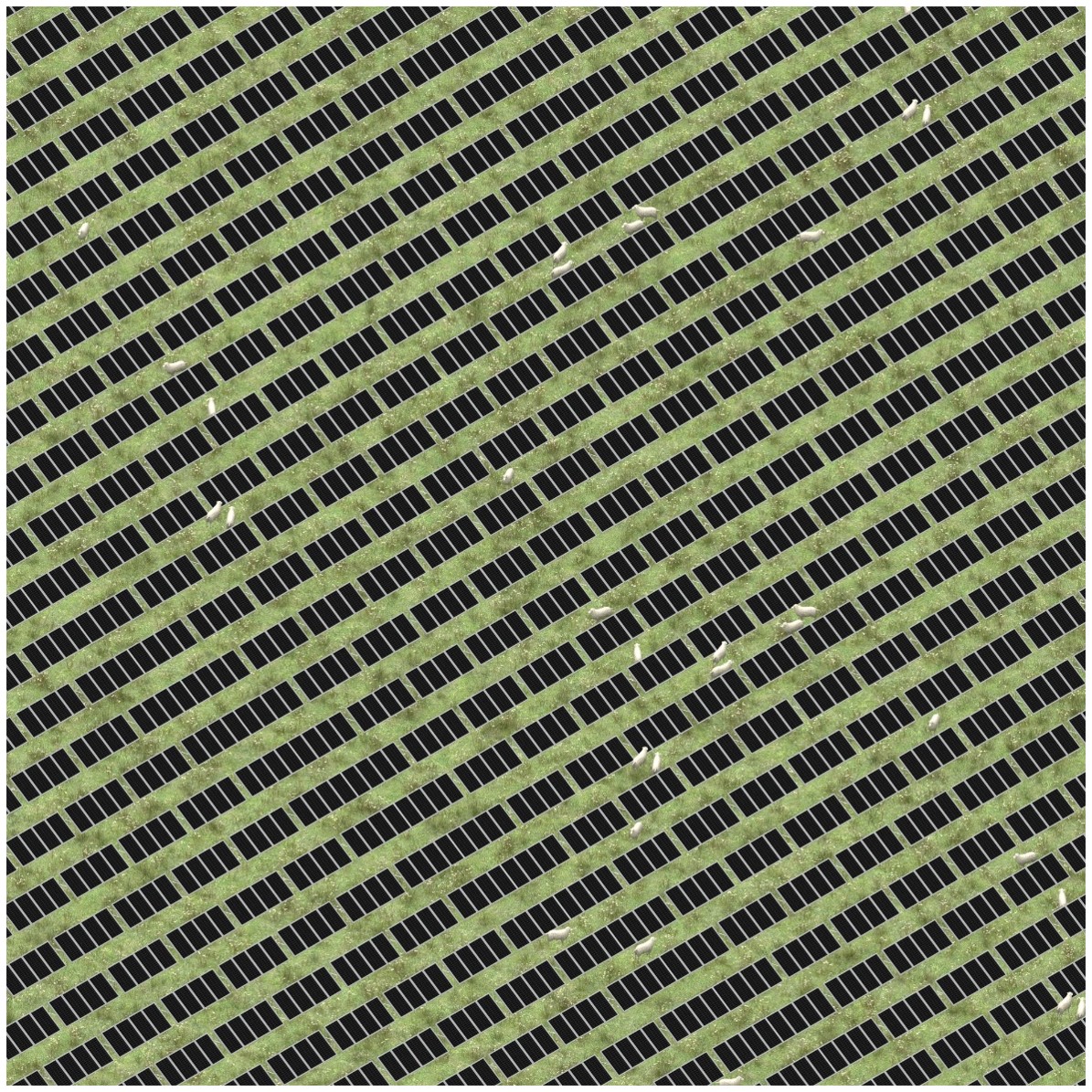

10,783,000kwh or what 7385 solar panels generate in a

year

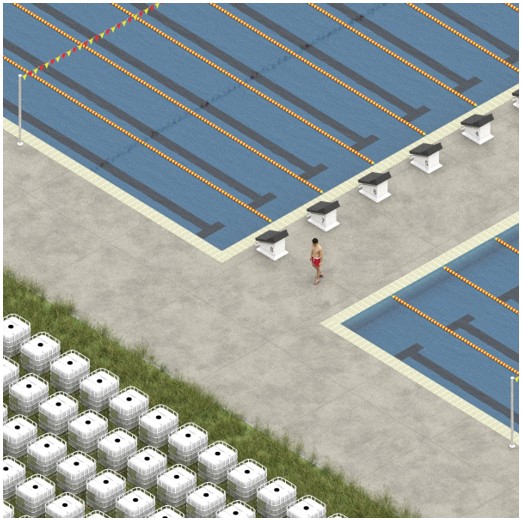

4,600,000lt or a little over 2 Olympic Swimming Pools

276,863kg

of CO2e or the CO2 emissions of the contents of 4

Petrol Tankers

We justify this architecture through perceived permanence, immortality and imperviousness, with little care for repair, tolerance of failure, the origin of the material and its end life. Much of this material as a result is destined for rapid downcycling or landfill and is a process that ignores the energy, labour and environmental impact of its production, construction and destruction.

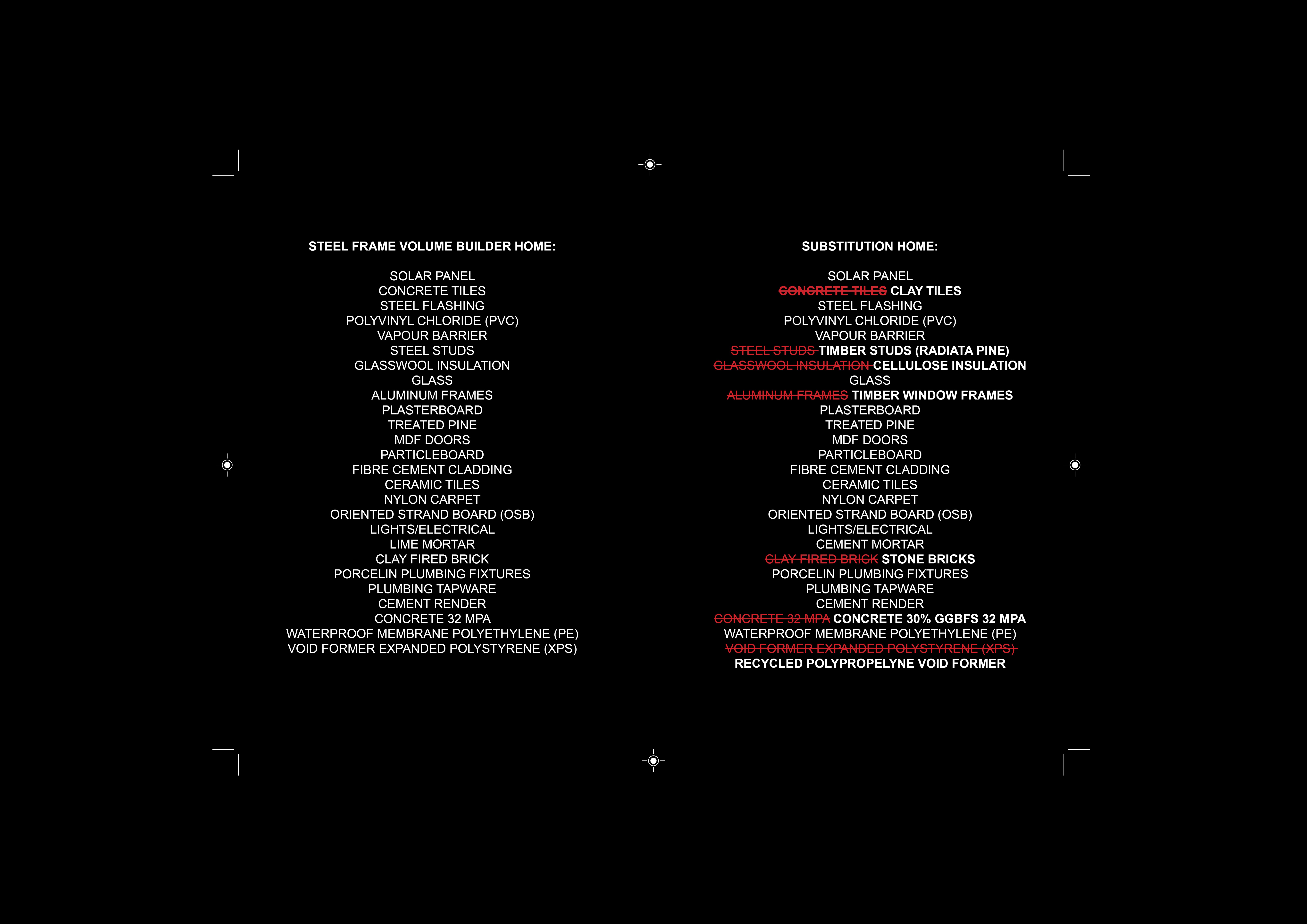

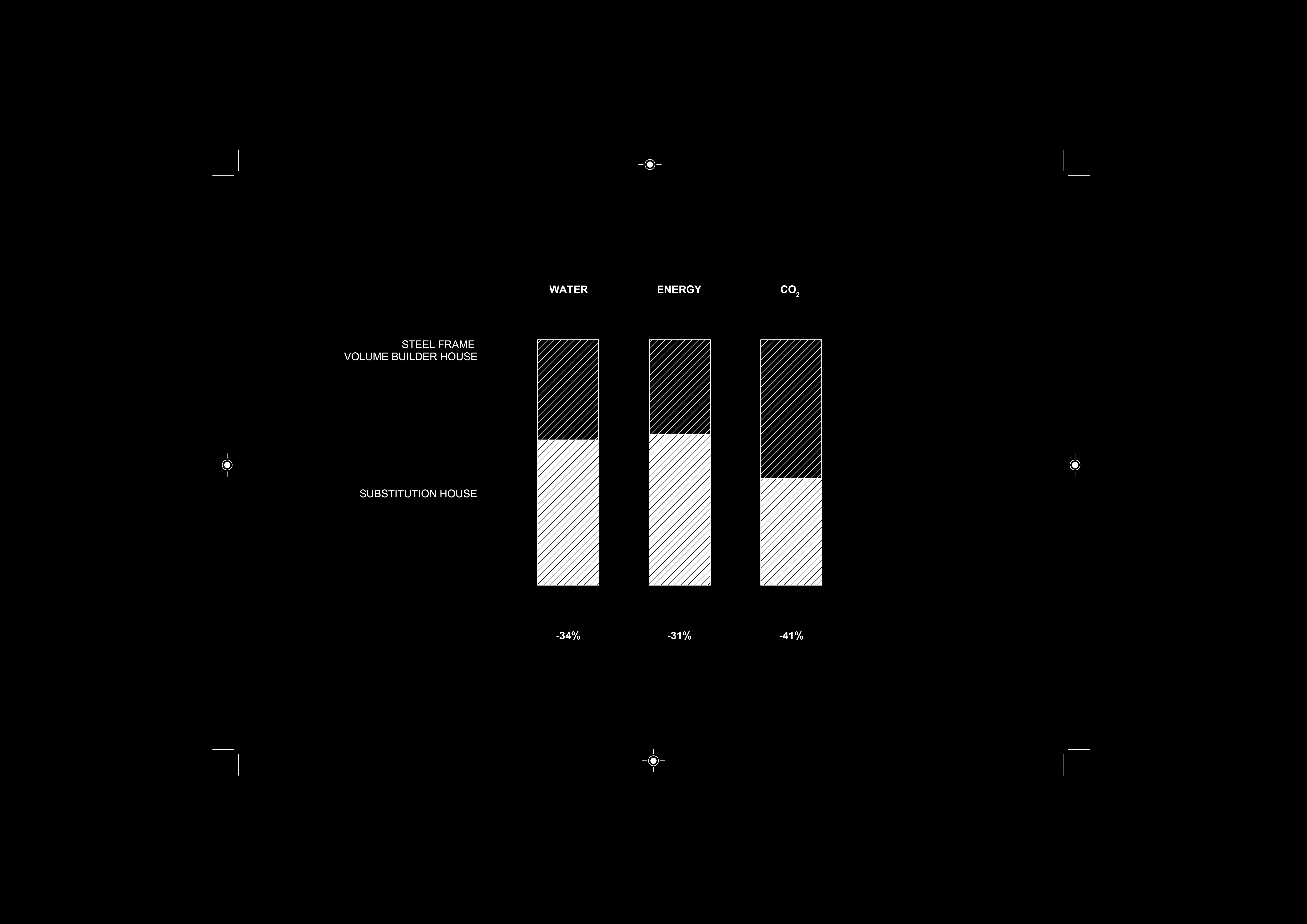

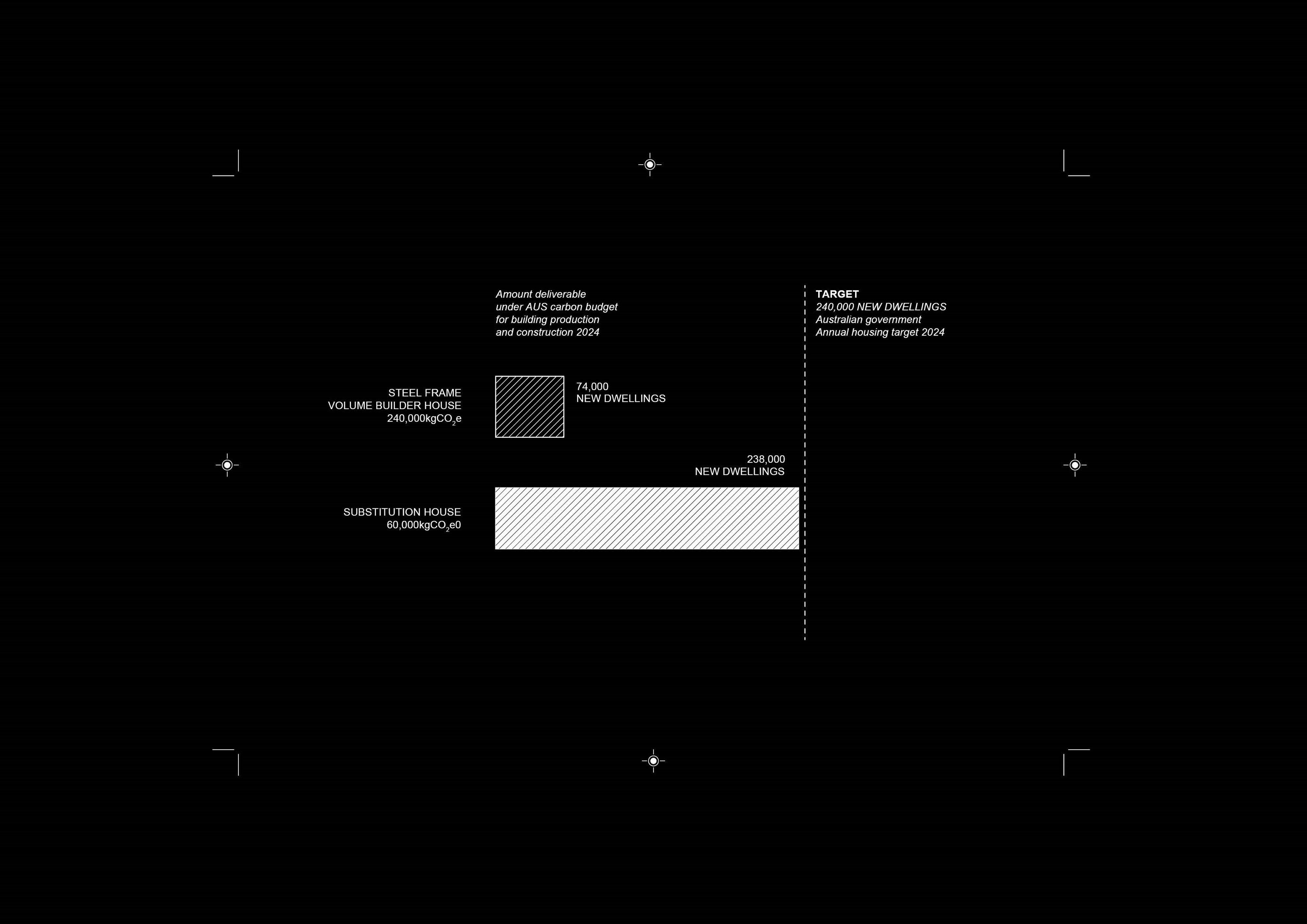

The construction industry’s version of reform is to see a less worse version of the same high-energy energy vastly extractive materials substituted in. This conception of reform ignores the need for new compositions, industries, products, resource and land management that cause regeneration and the reduction in consumption of finite materials we have become accustomed to. Replacing the heaviest emitting materials of the oil vernacular house whilst maintaining its appearance is significant but ultimately insufficient. It would lead to 41% reduction in carbon, 31% energy and 34% water. It is incapable of detaching our dependency on fossil fuels and reducing the ludicrous expenditure of energy. This is indicative of the ossified infrastructures of modern construction. When aggregated to be viewed against the federal government's duel ambitions for the construction of new dwellings and carbon reduction in 2024, these houses are evidence that fundamentally our construction industry must radically reform beyond that of substitution.

~ part II ~

intervening in the shadows

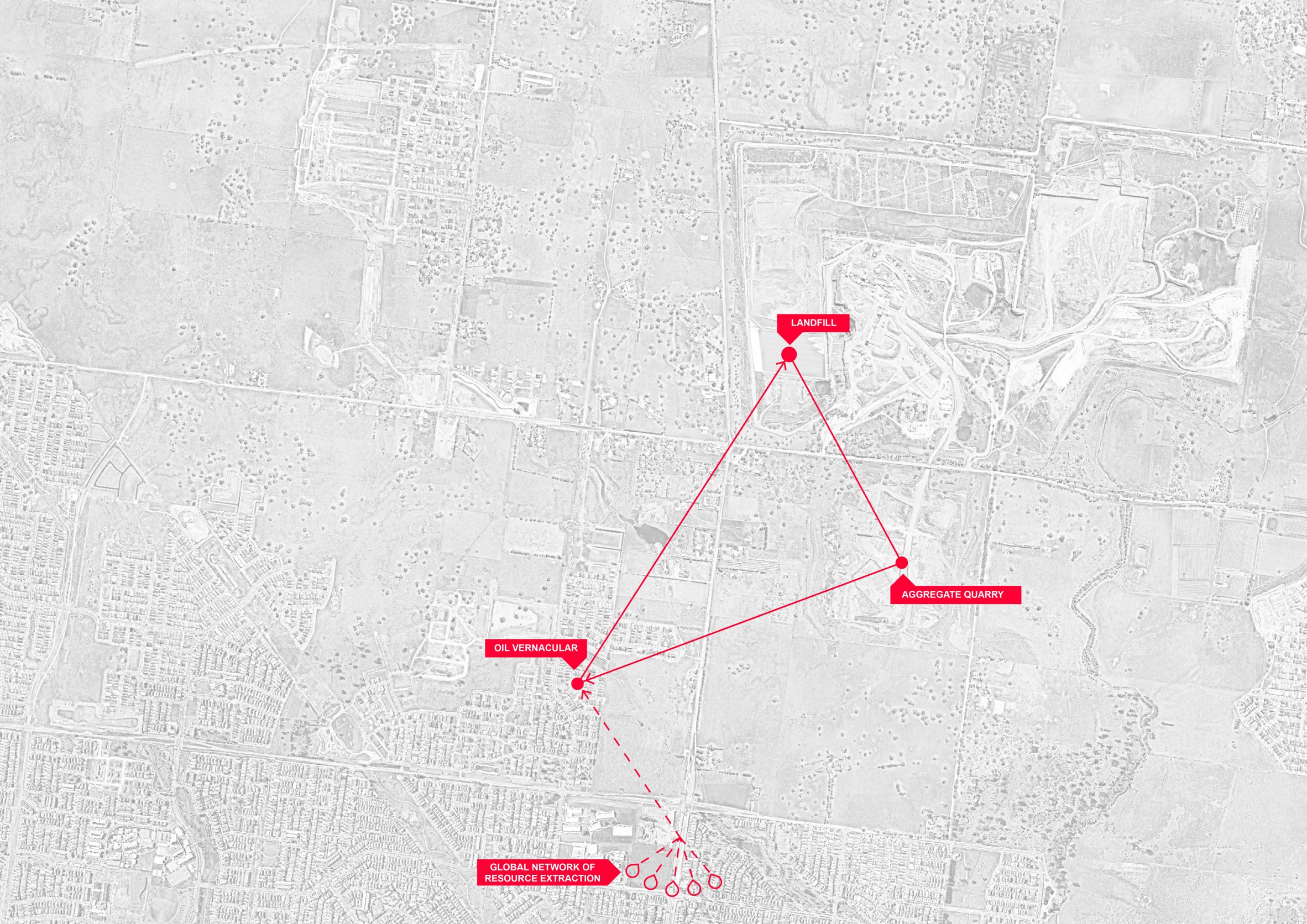

If we were to find an emblem of the problematic material culture we might find ourselves in Wollert at the peri-urban junction of Epping and Boundary Rd. A concrete aggregate quarry represents the insatiable thirst for resource extraction, oil vernacular houses, the additive objects of carbon dependency, reliant on a global network of resource extraction, and a landfill typifies the destination of much of the material of the oil vernacular. Should architecture take ownership of its environmental ramifications and make any attempt at remedying them it would do well to begin in a place like this. On this site, we might begin to unravel the tensions of the material production flow and consumption. As well as the implications of designing with wider material benefits and causations in mind. Both a site in need of material reform and a site to intervene.

To begin to reform our material culture is to first reckon with the materials we already have. While current practices lean softly on recycled goods this process generally requires masses of energy to reproduce and generally requires a process of rapid downcycling or a binding that can further inhibit further recycling. Whilst technological limitations exist for reuse, especially of the proprietary which denies repair. The first port of call for architecture is to use the materials and buildings we already have.

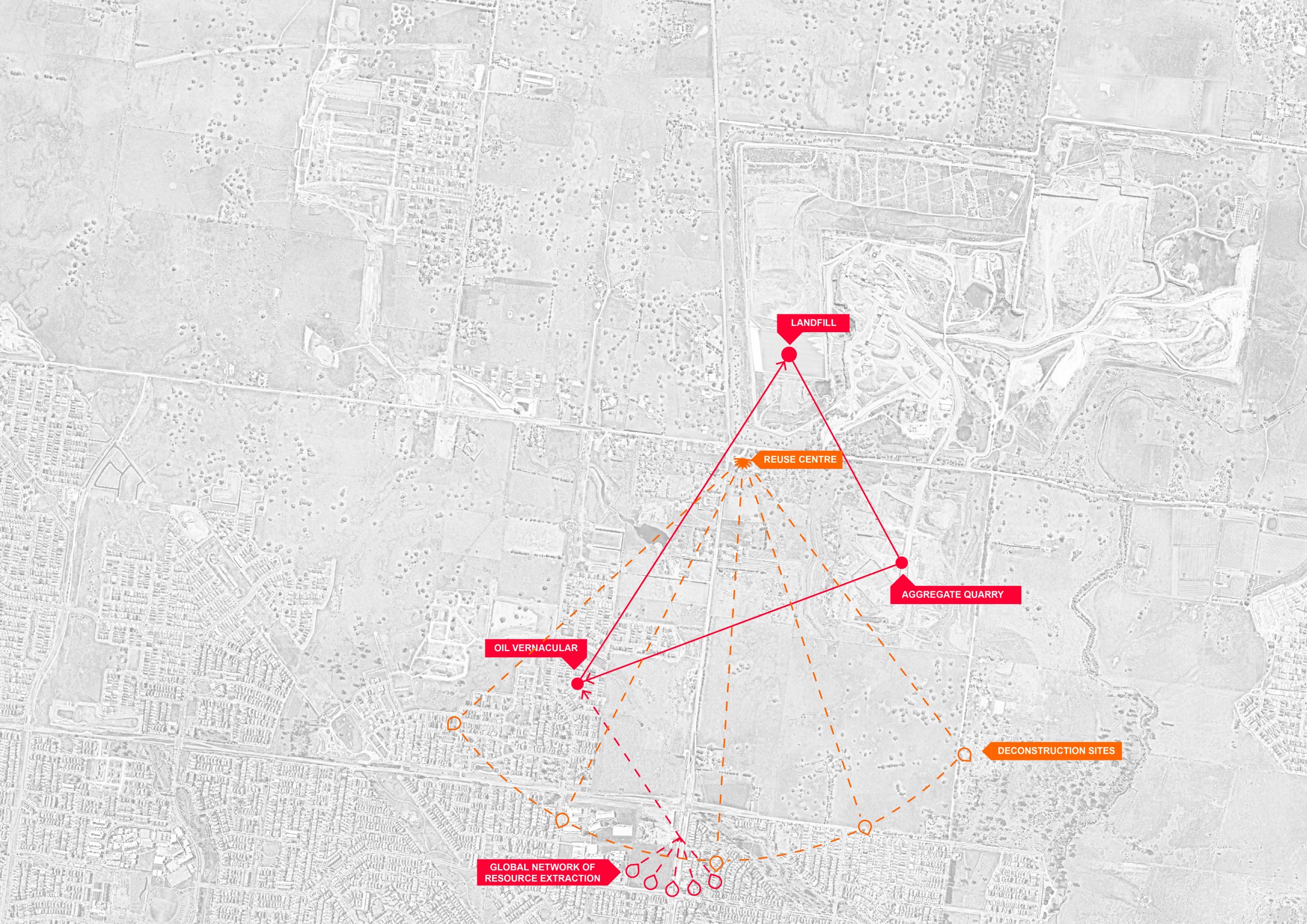

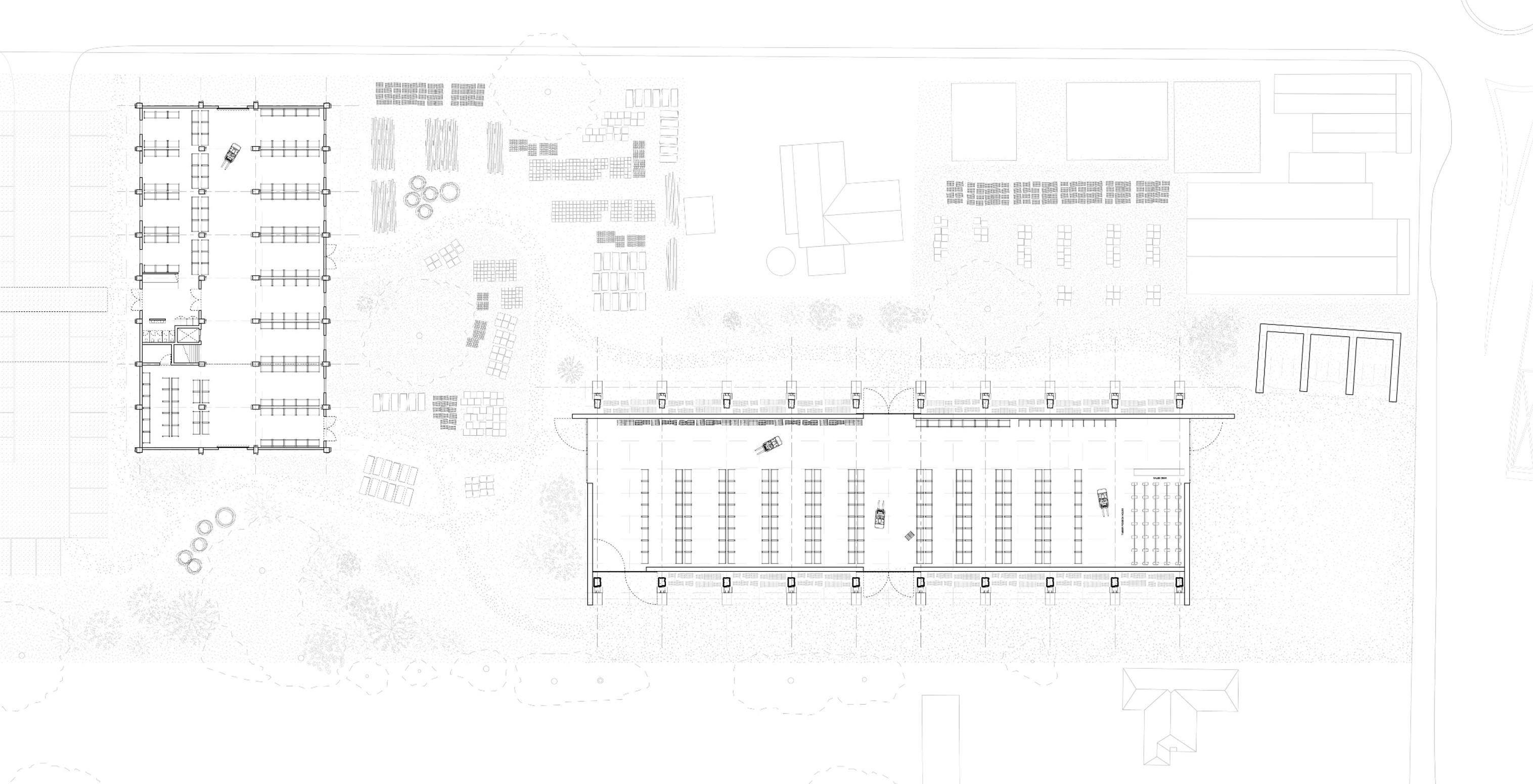

As an attempt to intervene on the disposability of construction industry a reuse centre is placed on the main road adjacent to the landfill and an existing salvage yard.

Its architecture sees the discarded built environment as an urban mine for the generation of form. Principal elements are taken from a cattle shed up for tender from the Ballarat showgrounds. Acknowledging its age and structural limitations the shed structure is split and slid with a two level volume inserted in between. This volume comes from recently dismantled parts of the Holden Plant at Fishermans Bend. The apertures and ground condition come from the windows and precast panels of the slated demolition site of RMIT Village, a mere five years after its completion. Other reuse elements are taken from existing reuse industries and opportunistic, frequently discarded elements. Bluestone curbs, spiral ducts, telegraph poles and roof tiles. This architecture holds the material memory of a broader territory, as much a cultural project as it is an environmental one. Its architecture is messy; it does not endear itself to the current aesthetics of seamless, geographically irrelevant architecture that pervades modern construction. It makes do with that which is available.

To view the benefits of this production would be to see landfill diversion, downcycle avoidance, and low energy production. A building born out of the perceived end of life breathes new air through a reconstitution, with an inevitable deconstruction designed into its assembly.

In plan, the building’s divisions follow the logic of material reuse, sorting, grading, cleaning, recording, reworking, testing, and recertifying before being brought to market. This process enables use within the construction industry and is housed on the ground with supporting functions above.

The logic of this material flow then dictates the spatial order of the building.

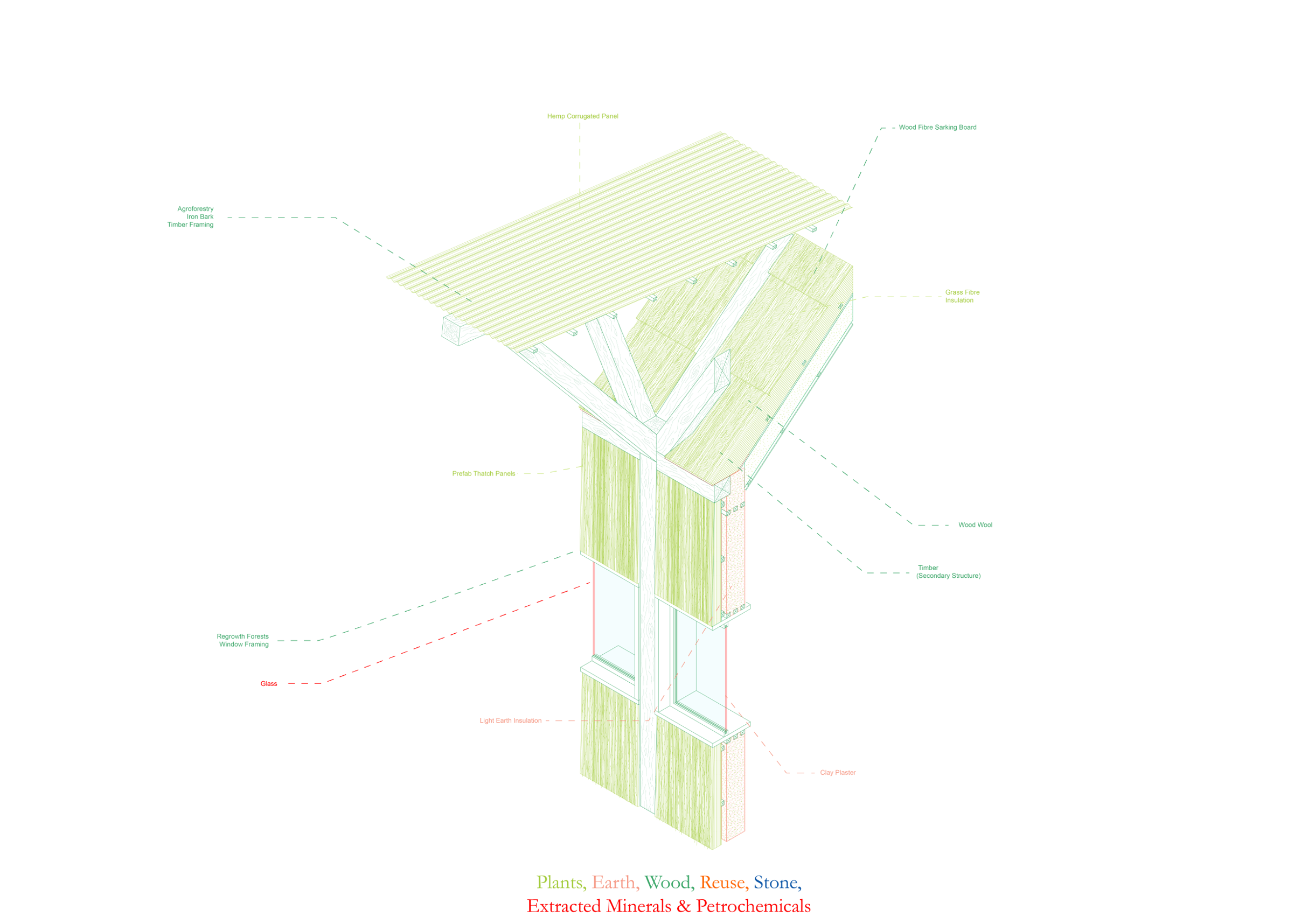

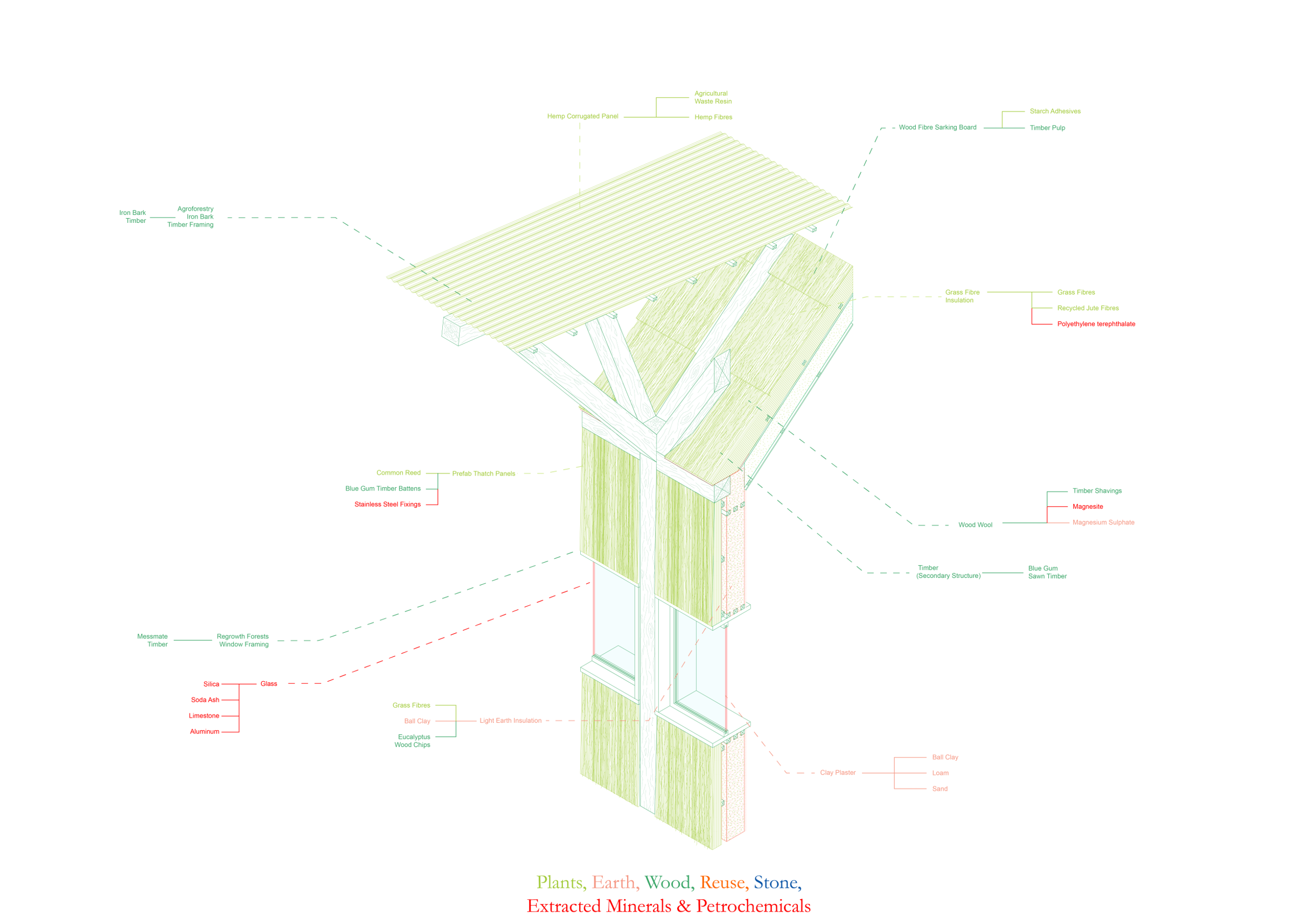

Inevitably though the act of reuse will be shown to be a meaningful contribution towards a new material paradigm it will be insufficient in totality due to natural wastage and the stubbornness of certain material forms. Subsequently, the input of new material will inevitably be required. If the assumptions are that this paradigm holds the needs outside of the territory alongside the needs of the object, it will require a considered bio-based approach. Utilising primarily the near occurrences of abundant biomass.

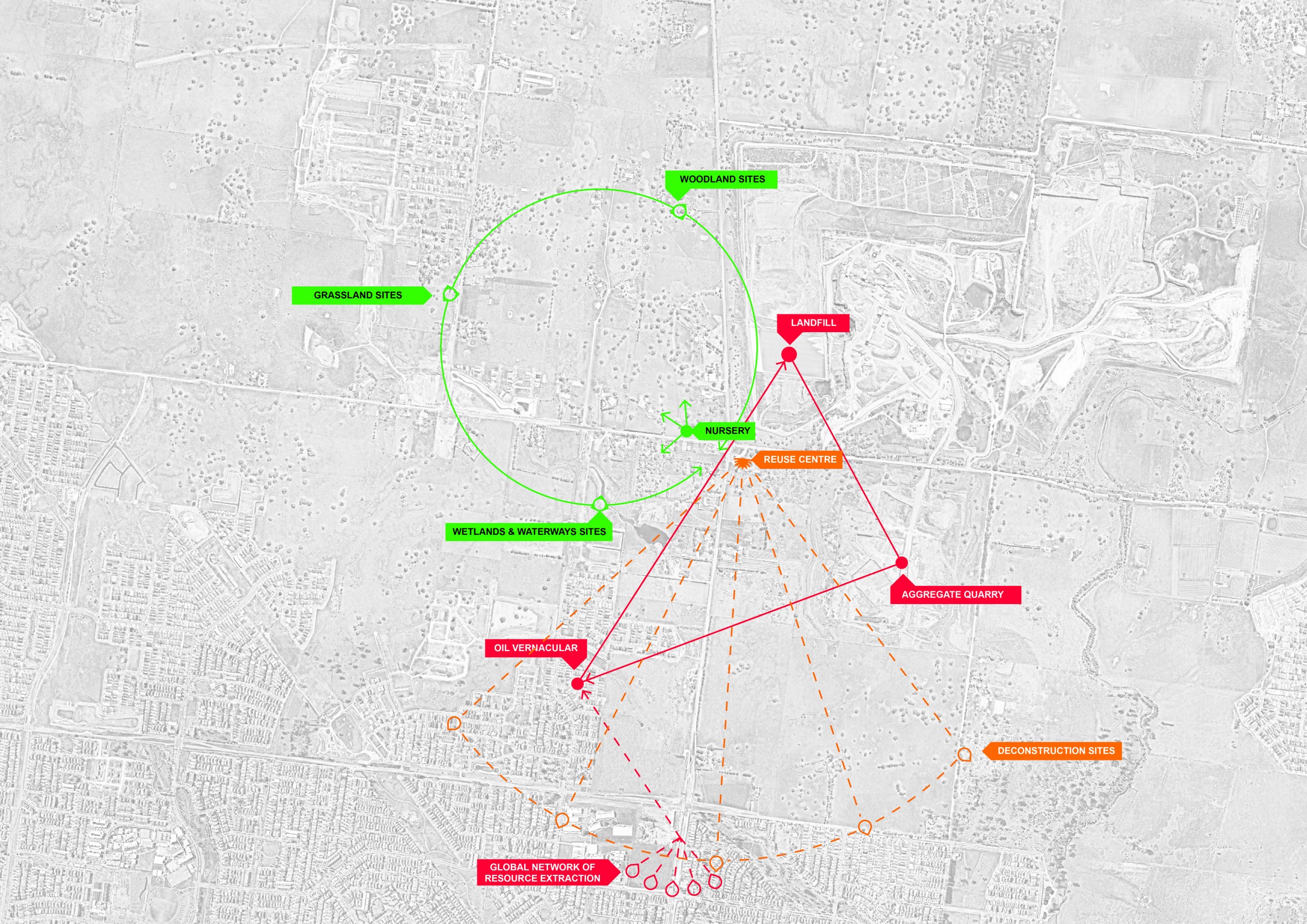

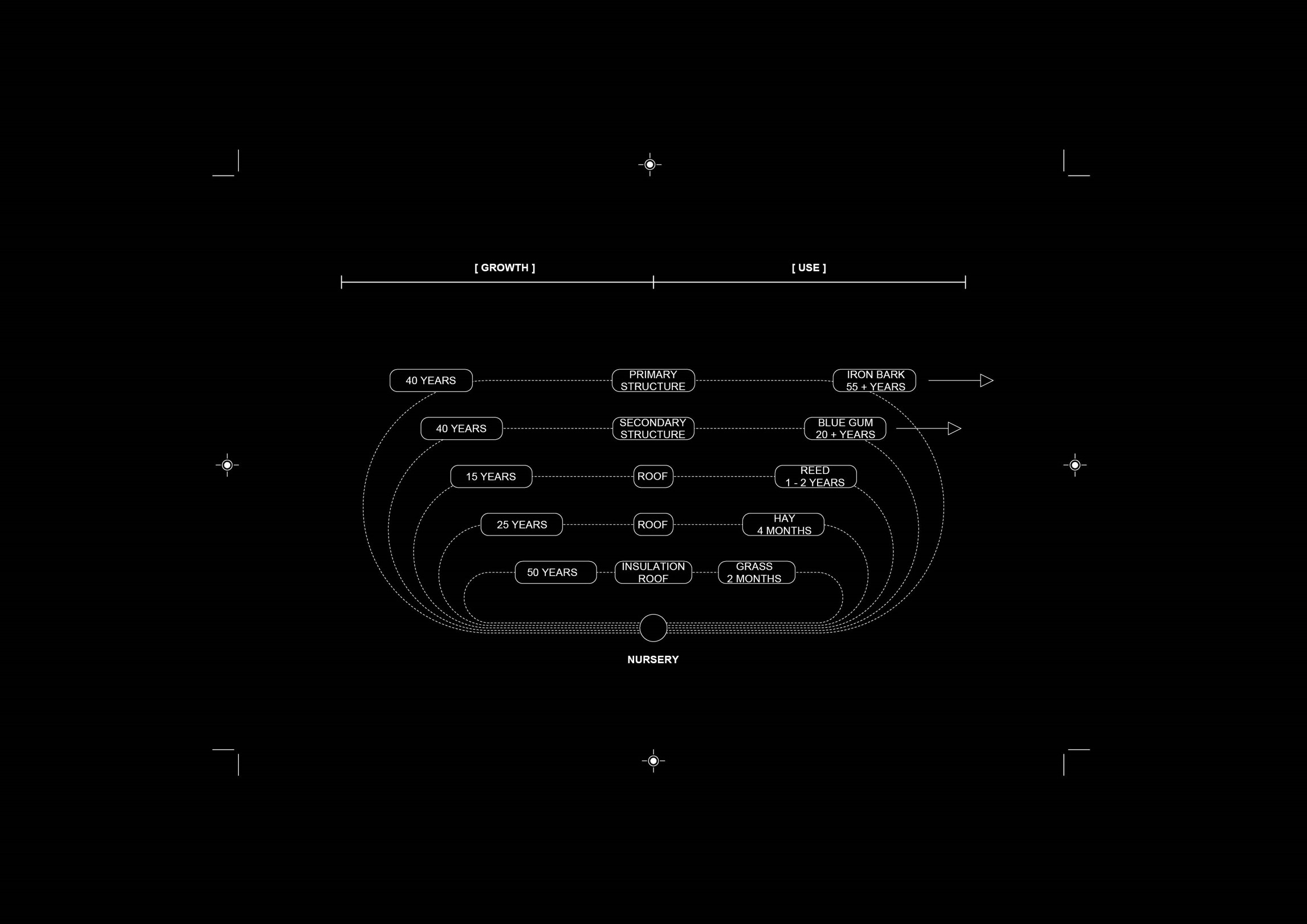

As a seeding point, a nursery is on the site for the intent purposes of seeding and disseminating the regionally relevant plants of local building culture, to the grasslands, woodlands and wetlands that can be found in the area. The problem of this architecture is however unlike the accustomed immediacy and consistency of resource extractivism, designing without depletion requires differing timelines based on cycles of growth, decay, maintenance and availability. Therefore the failure to seed this industry now will mean a failure to shift. The repeated failure of policy to enable this shift is apparent in the failed upscaling of forestry projects in which we have only recently broken the drought of 10 years without a new timber plantation in Victoria. Fundamentally this paradigm shift cannot be too reliant on singular resources and monocultures, it must mimic the tapestry of balanced landscapes. As a result, the architecture of this project takes its matter from varied sites of crop production, agroforestry, waterways, understory bushes, pulp plantations, and grasslands attempting to imbed the value of diversity of matter into the building’s composition.

Its architecture is that of an expandable grid. Acknowledging the required growth in the industry and selecting an architecture that feasibly enables it.

To examine one detail of this project we would see not only the components of the building but the material and plant logics implicit in the materiality, the outer wall clad in reed found on waterway edges protects from water and inherent material trait, a double roof ventilating the air cavity keeping the building climatically cool to not cause germination in the seed bank.

This detail shows the bio-region reflecting its surrounding ecology embedded in the building. This project is not just about the composition, the material, its make-up, or even the site it comes from.

This project is about the benefits that we might cause through our labour, seizing an opportunity to cause things outside the object, in the shadow places and broader territories. To see habitat reinstatement through a demand for grassland insulation. To cause soil regeneration or phytoremediation of toxins through a specified plant product or minimise water use, prevent timber from being pulped and having a fast return to the carbon cycle, or create long-term stores of carbon through biomass and agriculture waste by-products.

In our current predicament of materials, we often forget that until recently building was a deeply regional affair, based on the availability of local resources, the ease of extraction and processing and the rate of natural replenishment and abundance. Industrialization brought on a flattening of the heterogeneous towards a homogenous regionally indistinct carbon form.

The conceptive functions aforementioned will help form the production of a differing largely regionally distinct paradigm and a widely differing market. These buildings constitute the shift towards a regionally dependent retail for this trade expanding an existing small hardware store. In this paradigm, a reassociation of building and the shadow places of cultivation and production has occurred. Primarily composed of products of abundant bio-based material, reuse and waste products of the locality and construction industry. They do not express material where it is not required or demand unnecessary energy. These differing materials are cause for new opportunities of composition, expression and tectonics produced through the various techniques available. These uncanny adjacencies and specificities of territory and availability provide quirks of expression of material.

The buildings speak to role architects as authors of the object and the agency we have through the labour of documenting, specifying and constructing to act as the advocate for the object and its effects, both on the site and beyond.

Through the architect's labour, we should acknowledge that we form and can expand a market for goods, currently, this market is products that can be accessed easily at significant environmental cost.

The need to leave these products behind is urgent in the face of the climate crisis. Through the drawing and the specification, we may not only provide a convincing image of a new material culture but also set a demand aiding an ability to scale, disseminate and cause new industries. In turn, this industry and trade can cause a wide array of material benefits not only through the material properties it has but also the benefits of its production. Architecture’s hope at this moment is that through an engagement with the shadow places as part of the design lexicon, we might improve our relationship with the land.

In plan, the building is distinctly mundane in adhering to the prevailing planning of these types of spaces that were first enabled by the use of fossil fuels. The architecture of the building encases various climatic conditions required for material storage determined by requirements of shelter and susceptibility. The products flow in and out, a choreography on the site.

The building acts as the anchor to the reform of a wider territory encompassing, agriculture, land management, deconstruction and extraction. It is the place where we might access the possibilities of this thinking.

To look at the detail of this project we see an example of material logic and reasonable resource extraction. The stone column minimally cut used in compression reduces the energy required for production, its retention as colossal enables further reuse and recycling and promotes tolerance of imperfection. It places a stark contrast to the current extraction of the aggregate quarry which currently detonates the rock immediately placing it as the least valuable and worst performing resource of stone possible.

This architecture is not without its compromises nor does it pretend to hold any unique silver bullets but in the sobering realisation of our untenable ways, it seeks to trudge the path of progress. With the architect acting as an agent of decarbonisation and regeneration, we can hope to influence the market of construction towards a differing material paradigm.

~ part III ~

a house in Wollert

The moment we will know success within a new material culture will not be in the exemplary projects but rather in the mundane projects in which the profession did not touch. The broader reform will be evident in a wide-reaching material culture of place where an expanded notion of what things are costing implicitly and explicitly are accounted for. Perhaps it might be evident in the details of a volume builder home.

Where we might see the reuse of glass doors and bricks implemented to form a winter garden, a plan divided into thermal zones, or a detail showing a stone plinth with the Victorian straw insulating the building, or the timber from a habitat reinstating agroforestry source.

This would represent the disintegration of our existing paradigm, one that thrives off the dual logics of extraction and abstraction that form a detachment from the material landscapes and represent a retreat from the responsibilities of reality. If we re-engage with our responsibilities and causations we might ultimately rethink our cities, our homes and our lives, and have a profoundly less parasitic relationship with the land.

This project seeks to see the reality of our situation and offer a counter-future of optimism in the face of terrifying repercussions. It is not without challenge, the ossified infrastructures of the construction industry are risk-averse and resist change, neglecting the true risk of not changing. This type of design will only be possible upon reform of the codes and standards that govern construction to include the novel alternative materials that constitute these buildings of which they currently sit outside of the protection of.

This manner of design inverts and broadens the gaze of the architect, holding a multiplicity of material landscapes as part of the project's responsibility; it stipulates design through an ethics of material and logic.

It sees itself within not only the object but its shadow.

professional experience

work 2024 {{

+ - (thesis)

new hearth

work 2023 **

pirroette

babble

work 2022 >>

in a perfect world

i wouldn’t be here

work 2021 ::

_lo.ading

clumsy x _lo.ading

work 2020 //

degrowthtorium

snapback, caliper, shift 06

work 2019 ::

ambr

work 2018 ~~

glitch

fragments

destruction of mosul

the learned bathroom

— The Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung people are the traditional custodians of this land and waters of the place I reside and work. I acknowledge that this land is unceded and soverign land.